How to sell a percentage of your business? It’s a question many entrepreneurs grapple with, a strategic move that can inject capital, fuel growth, or simply provide an exit strategy. This guide unravels the complexities of this process, from meticulously determining your business’s valuation to navigating the often-tricky waters of investor negotiations and post-sale considerations. We’ll equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions and successfully secure the best possible deal.

Successfully selling a portion of your company requires a multifaceted approach. Understanding valuation methodologies, structuring the sale strategically, identifying and vetting potential investors, and skillfully negotiating terms are all crucial elements. This guide will delve into each stage, providing practical advice, real-world examples, and actionable strategies to help you achieve your financial goals while maintaining control over your business’s future.

Determining Valuation

Accurately valuing your business is crucial before selling a percentage. An incorrect valuation can lead to unfavorable terms and a loss of potential profit. Several methods exist, each with its strengths and weaknesses, depending on the specifics of your business. Understanding these methods will empower you to negotiate a fair price.

Business Valuation Methods

Choosing the right valuation method depends on your business’s characteristics, such as its stage of development, profitability, and asset base. The following table summarizes three common approaches:

| Method | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) | Projects future cash flows and discounts them back to their present value. This method focuses on the business’s ability to generate future earnings. | Considers future growth potential, provides a comprehensive valuation. | Requires accurate financial projections, sensitive to discount rate assumptions. |

| Asset-Based | Values the business based on the net asset value of its tangible and intangible assets. This is often used for businesses with significant physical assets. | Relatively simple to calculate, provides a floor valuation. | Ignores the business’s earning potential, may undervalue businesses with significant intangible assets (like brand recognition). |

| Market-Based (Comparable Company Analysis) | Compares the business to similar companies that have recently been sold or are publicly traded. The valuation is based on multiples of key financial metrics (e.g., revenue, EBITDA). | Relatively straightforward, leverages market data. | Finding truly comparable companies can be difficult, relies on the accuracy of market data. May not accurately reflect unique aspects of your business. |

Industry Benchmarks and Comparable Transactions

Industry benchmarks, such as average revenue multiples or profit margins for similar businesses, provide a valuable context for your valuation. Comparable transactions, meaning the sale prices of similar businesses, offer even more concrete data points. For example, if similar businesses in your industry recently sold for 5x their annual revenue, this suggests a potential range for your own valuation. However, it’s crucial to adjust for any significant differences between your business and the comparables.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Valuation Example

Let’s assume a business projects the following free cash flows (FCF) for the next five years: Year 1: $100,000; Year 2: $120,000; Year 3: $150,000; Year 4: $180,000; Year 5: $200,000. We’ll use a discount rate of 10%. The terminal value, representing the value of the business beyond year 5, is estimated at $3,000,000.

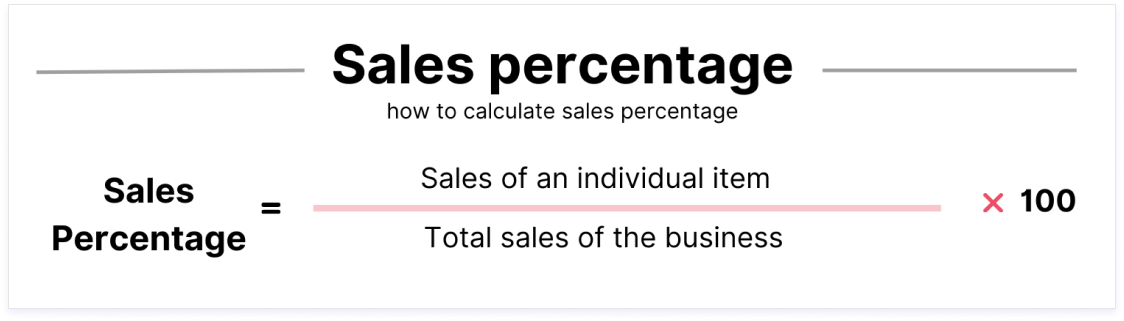

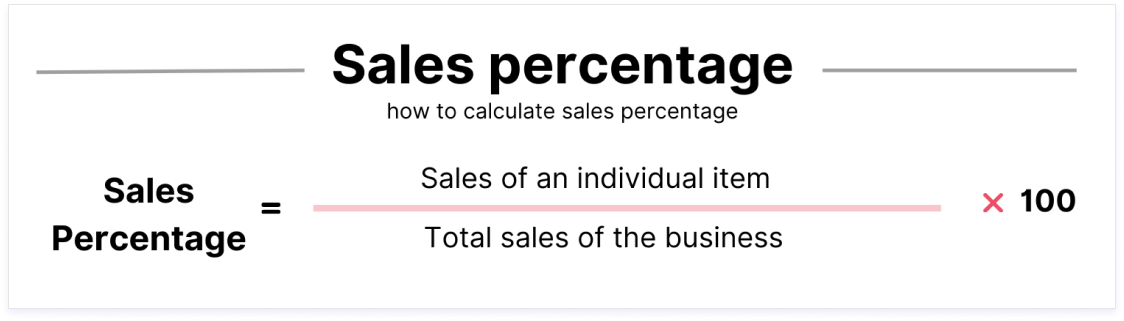

To calculate the present value of each year’s FCF, we use the formula: PV = FCF / (1 + r)^n, where PV is present value, FCF is free cash flow, r is the discount rate, and n is the number of years.

The present value of the cash flows would be:

Year 1: $100,000 / (1 + 0.1)^1 = $90,909

Year 2: $120,000 / (1 + 0.1)^2 = $99,174

Year 3: $150,000 / (1 + 0.1)^3 = $112,697

Year 4: $180,000 / (1 + 0.1)^4 = $124,184

Year 5: $200,000 / (1 + 0.1)^5 = $124,184

The present value of the terminal value is: $3,000,000 / (1 + 0.1)^5 = $1,862,356

Summing these present values gives a total enterprise value of approximately $2,543,396. This represents the total value of the business, including debt. To find the equity value, you would subtract any outstanding debt.

Growth Potential’s Impact on Valuation

Consider two identical businesses, except one is expected to experience significant growth in the next five years, while the other anticipates stagnant growth. The high-growth business will project substantially higher future cash flows, leading to a significantly higher valuation using the DCF method. For instance, if the high-growth business projects 20% annual growth instead of the 10% used in the previous example, the resulting valuation would be considerably larger, reflecting investor enthusiasm for its future potential. This illustrates how growth projections directly influence a business’s valuation.

Structuring the Sale: How To Sell A Percentage Of Your Business

Selling a percentage of your business involves more than just agreeing on a price. A well-structured sale requires careful consideration of legal implications, ownership structures, investment vehicles, and the creation of a comprehensive agreement. Overlooking any of these aspects can lead to significant financial and legal repercussions down the line.

Legal Implications of Selling a Business Percentage

The legal ramifications of selling a portion of your business are substantial and vary depending on several factors, including your business structure, the jurisdiction where your business operates, and the specifics of the sale agreement. Key legal considerations include compliance with securities laws (particularly if selling to multiple investors), intellectual property rights transfer, non-compete agreements, and potential liabilities associated with the business. It is crucial to consult with experienced legal counsel specializing in business transactions to ensure all legal requirements are met and your interests are protected throughout the process. Failure to do so could result in costly litigation or invalidate the entire transaction.

Impact of Ownership Structures on the Sale

The legal structure of your business significantly impacts how you sell a percentage. Different structures have varying implications for taxation, liability, and the ease of transferring ownership.

- Limited Liability Company (LLC): LLCs offer liability protection to the owners while providing flexibility in management and taxation. Selling a percentage of an LLC typically involves transferring membership interests. The sale agreement should clearly define the rights and responsibilities of the remaining and new members.

- S-Corporation (S-corp): S-corps pass corporate income directly to the shareholders, avoiding double taxation. Transferring shares in an S-corp requires careful consideration of shareholder agreements and potential tax implications for both the seller and buyer.

- C-Corporation (C-corp): C-corps are taxed separately from their shareholders. Selling shares in a C-corp involves transferring ownership of stock, subject to the corporation’s bylaws and any relevant shareholder agreements. This structure can be more complex to navigate legally.

Choosing the right structure beforehand can simplify the sale process significantly. For example, an LLC’s operational flexibility might make it easier to structure the sale agreement compared to the more rigid framework of a C-corp.

Investment Vehicles for Business Percentage Purchases

Several investment vehicles can be used to acquire a percentage of a business. Each has its own implications for the seller and buyer.

- Equity: This involves selling a direct ownership stake in the business in exchange for capital. Equity investments provide the buyer with a share of the company’s profits and losses, and voting rights (depending on the class of shares).

- Convertible Notes: These are debt instruments that can be converted into equity at a future date, often under specific conditions. Convertible notes offer investors a return on their investment (interest) while providing an option to become equity holders if the company performs well. They can be particularly attractive to early-stage investors.

The choice of investment vehicle should be determined based on the investor’s preferences, the stage of the business, and the seller’s goals. For instance, a later-stage business might favor equity financing, while an early-stage company might find convertible notes more suitable.

Creating a Legally Sound Sale Agreement

A comprehensive and legally sound sale agreement is essential to protect both the buyer and the seller. The agreement should clearly define:

- The percentage of ownership being sold.

- The purchase price and payment terms.

- The transfer of assets and liabilities.

- Representations and warranties made by the seller.

- Covenants and restrictions on the parties.

- Dispute resolution mechanisms.

A well-drafted sale agreement should anticipate potential future issues and provide clear solutions. Ignoring this critical step can lead to costly disputes and legal battles.

It’s highly recommended to involve legal counsel experienced in business transactions to draft and review the agreement, ensuring all aspects are legally sound and protect your interests. The cost of legal expertise is far outweighed by the potential risks of an inadequately drafted agreement.

Finding and Vetting Investors

Selling a percentage of your business requires securing the right investor. This involves identifying potential investors, conducting thorough due diligence, and asking crucial questions to ensure a mutually beneficial partnership. The process demands careful consideration and strategic planning to achieve a successful outcome.

Investor Types

Different investor types possess unique investment strategies, risk tolerances, and expectations. Understanding these differences is crucial for targeting the most suitable partners. Angel investors, typically high-net-worth individuals, often invest smaller amounts in early-stage companies, focusing on high-growth potential. Venture capitalists (VCs) invest larger sums in companies with demonstrably strong growth trajectories, usually seeking significant returns within a defined timeframe. Private equity firms, on the other hand, invest in more established businesses, often focusing on operational improvements and restructuring to maximize value. The ideal investor type depends heavily on your business’s stage of development, financial needs, and long-term goals.

Resources for Finding Investors

Locating suitable investors requires a multi-faceted approach. Online platforms dedicated to connecting businesses with investors, such as Gust, AngelList, and Crunchbase, offer valuable resources. Networking events, industry conferences, and business incubators provide opportunities to connect with potential investors directly. Leveraging your existing professional network, including mentors, advisors, and former colleagues, can also yield promising leads. Finally, working with investment bankers specializing in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) can significantly enhance your chances of finding the right investor. These bankers possess extensive networks and expertise in navigating the complexities of equity financing.

Due Diligence Process

Due diligence is a critical stage, involving a thorough investigation of both the business and the potential investor. From the seller’s perspective, this involves preparing comprehensive financial statements, demonstrating a clear business plan, and showcasing the company’s intellectual property and competitive advantages. The seller should also proactively address potential risks and liabilities. From the buyer’s perspective, due diligence focuses on validating the financial projections, assessing the management team’s competence, and verifying the legal compliance and regulatory status of the business. This often includes independent audits, legal reviews, and market research. A thorough due diligence process minimizes risks and fosters trust between both parties.

Key Questions for Potential Investors

Before committing to a partnership, it’s crucial to ask potential investors key questions to assess their suitability and alignment with your business goals. These questions should cover their investment philosophy, their expected return on investment (ROI), their level of involvement in the business’s operations, and their exit strategy. Inquiring about their past investment experiences, their understanding of your industry, and their long-term vision for the company is also essential. Clarifying their expectations regarding governance, reporting requirements, and future funding rounds ensures transparency and avoids potential conflicts. For example, a key question might be: “What is your typical investment horizon for companies in this sector?” This provides insight into their long-term commitment and compatibility with your business’s growth trajectory. Another crucial question is: “What are your expectations regarding board representation and management involvement?” This helps clarify their level of influence and potential operational interference.

Negotiating the Deal

Negotiating the sale of a percentage of your business requires a strategic approach, balancing your desired outcome with the investor’s expectations. A successful negotiation hinges on thorough preparation, understanding your company’s value, and possessing strong communication skills. This section will Artikel common strategies and tactics, explore various deal structures, and demonstrate how to craft a compelling investor presentation.

Common Negotiation Strategies and Tactics

Effective negotiation involves more than just haggling over price. It’s about understanding your leverage, identifying the investor’s priorities, and finding mutually beneficial solutions. Common strategies include anchoring (setting a high initial price to influence the negotiation), concession sequencing (making smaller concessions later in the negotiation), and employing a “walk-away” strategy (demonstrating your willingness to forgo the deal if your terms aren’t met). Tactics such as framing (presenting information in a way that emphasizes your company’s strengths), and building rapport (establishing trust and understanding with the investor) are also crucial. For example, a company with strong revenue growth might anchor their valuation higher than a company with lower growth, but be prepared to make concessions based on the investor’s risk tolerance and due diligence findings.

Examples of Different Deal Terms

Several deal structures exist, each with its implications. A simple approach involves setting a price per share, based on a pre-determined valuation. Alternatively, valuation multiples (such as revenue multiples or EBITDA multiples) are often used, particularly in early-stage companies where profits are not yet substantial. For instance, a company with $1 million in revenue might be valued at 3x revenue, resulting in a $3 million valuation. Equity stakes represent the percentage of ownership being sold. For example, selling 20% equity in a $3 million company means the investor invests $600,000. The deal terms should clearly define the ownership structure, voting rights, and liquidation preferences.

Creating a Compelling Investor Presentation

A well-structured presentation is essential for attracting investors. It should clearly articulate your company’s vision, market opportunity, business model, financial projections, and team expertise. Visual aids, such as charts and graphs, are helpful in conveying key data points effectively. The presentation should highlight the unique value proposition of your company and the potential for significant returns on investment. A compelling narrative that emphasizes the problem your company solves, your market leadership position, and your strong financial outlook is key to capturing investor attention and building confidence. Consider including case studies or testimonials to further strengthen your presentation.

Potential Deal-Breakers and Mitigation Strategies

Understanding potential deal-breakers is crucial for a smooth negotiation. Proactive planning can help mitigate these risks.

| Deal Breaker | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

| Unrealistic Valuation Expectations | Conduct thorough market research, provide robust financial projections, and be prepared to justify your valuation with comparable company data. |

| Disagreements on Control and Governance | Clearly define ownership structure, voting rights, and board representation in the term sheet. |

| Lack of Due Diligence Access | Provide full transparency and open access to all relevant financial and operational information. |

| Conflicting Investor Interests | Clearly Artikel investor rights and responsibilities in the term sheet and ensure alignment with your company’s long-term goals. |

| Unfavorable Legal Terms | Engage experienced legal counsel to review and negotiate all legal documents. |

Post-Sale Considerations

Selling a percentage of your business is a significant milestone, but it’s not the end of the journey. The post-sale period requires careful planning and ongoing commitment from both the seller and the buyer to ensure a successful and mutually beneficial partnership. This phase is crucial for maintaining the value of the business and fostering a productive working relationship.

The ongoing responsibilities of both parties are multifaceted and require proactive management. Failure to address these responsibilities effectively can lead to conflict, diminished business performance, and ultimately, the unraveling of the partnership.

Ongoing Responsibilities of Seller and Buyer

Following the sale, both the seller and the buyer assume distinct yet interconnected responsibilities. The seller, even with a reduced ownership stake, often retains a significant role in the business’s operations, particularly during the transition period. This might involve mentorship, strategic guidance, or continued operational oversight depending on the terms of the agreement. The buyer, on the other hand, assumes the responsibility of managing the acquired portion of the business, integrating it into their existing operations (if applicable), and driving growth. Clear delineation of these roles, Artikeld in the sale agreement, is essential to prevent misunderstandings and conflicts. For example, a seller might be responsible for introducing the buyer to key clients and staff, while the buyer is responsible for implementing new marketing strategies.

Maintaining Communication and Collaboration

Open and consistent communication is paramount for a successful post-sale partnership. Regular meetings, progress reports, and transparent financial reporting are essential for building trust and addressing concerns promptly. A well-defined communication plan, agreed upon before the sale is finalized, can prevent misunderstandings and facilitate efficient problem-solving. This might involve weekly check-in calls, monthly performance reviews, and quarterly strategic planning sessions. Establishing clear communication channels and protocols from the outset is critical. For instance, a shared online platform for document sharing and communication could be invaluable.

Potential Post-Sale Challenges and Mitigation Strategies, How to sell a percentage of your business

Several challenges can arise after the sale of a business stake. One common challenge is differing visions for the future direction of the company. To mitigate this, the sale agreement should include clear objectives and strategies for the business’s growth. Regular reviews of progress against these objectives can help identify and address diverging viewpoints early on. Another potential challenge is disagreements over financial matters, such as profit sharing or investment decisions. Establishing a clear and transparent financial reporting system, with agreed-upon metrics and reporting frequency, is crucial for preventing such conflicts. Finally, disagreements about operational matters, such as hiring decisions or marketing strategies, can also arise. To mitigate this, the sale agreement should clearly define decision-making processes and responsibilities for different areas of the business. For example, a joint decision-making committee could be established to address major operational decisions.

Managing the Transition of Ownership and Responsibilities

A well-defined transition plan is critical for a smooth handover of ownership and responsibilities. This plan should Artikel a timeline for the transfer of knowledge, responsibilities, and assets. It should also include provisions for ongoing support from the seller during the transition period. For example, the plan might involve a phased handover of key client relationships, a mentorship program for key employees, and a detailed training program for the buyer on critical business processes. A clearly defined timeline, with specific milestones and responsibilities, will help ensure a smooth and efficient transition. This plan should be documented and agreed upon by both parties before the sale is finalized. Failure to plan this phase effectively can result in operational disruptions, loss of key personnel, and decreased business performance.

Illustrative Examples

Understanding the practical application of selling a percentage of your business is crucial. The following examples illustrate the process, potential outcomes, and the importance of careful negotiation. These scenarios are simplified for clarity but highlight key considerations.

Successful Partial Sale to an Angel Investor

This example details the journey of Sarah, a small business owner of a handcrafted jewelry company, who successfully sold a 20% stake to an angel investor.

- Valuation: Sarah engaged a business valuation expert who determined her company’s fair market value to be $500,000 based on revenue, growth potential, and comparable businesses. The 20% stake was therefore valued at $100,000.

- Investor Search: Sarah leveraged her network and online platforms to connect with potential angel investors. She prepared a detailed business plan, highlighting her company’s strengths, market position, and future projections.

- Due Diligence: The chosen investor conducted thorough due diligence, reviewing Sarah’s financial statements, legal documents, and operational procedures. This involved examining sales records, inventory levels, and customer contracts.

- Negotiation and Term Sheet: Sarah and the investor negotiated the terms of the investment, including the valuation, equity stake, investor rights, and exit strategy. A formal term sheet Artikeld the key agreements.

- Legal Documentation: Both parties engaged legal counsel to draft and review the final investment agreement, ensuring all aspects were legally sound and protected their interests.

- Closing: The transaction closed with the investor transferring $100,000 to Sarah in exchange for a 20% equity stake in her company. The new investor joined the board of directors.

Equity Structure After Partial Sale

The following visual representation describes a typical equity structure after a partial sale. Imagine a pie chart representing 100% ownership.

The pie chart would be divided as follows: Sarah (the founder) would retain 80% ownership, represented by a significantly larger slice. The angel investor would own the remaining 20%, depicted as a smaller, but still substantial, slice. This visual clearly illustrates the distribution of ownership after the investment. There would be no other slices, indicating no other shareholders at this stage.

Unfavorable Negotiation Terms and Consequences

Imagine Mark, owner of a software startup, hastily accepted an investment offer with unfavorable terms. He agreed to a low valuation of his company, resulting in a significant dilution of his ownership. Additionally, the investor secured excessive control rights, including veto power over key decisions.

- Low Valuation: The low valuation meant Mark received less capital than his company was truly worth. This limited his ability to scale the business and achieve its full potential.

- Excessive Control: The investor’s extensive control rights hindered Mark’s operational flexibility and decision-making autonomy. Disagreements arose frequently, leading to conflicts and delays.

- Limited Exit Strategy: The agreement lacked a clear exit strategy, leaving Mark with limited options for selling his remaining stake in the future. This reduced the overall value of his investment.

- Loss of Control: The investor’s significant influence eventually led to Mark’s removal from his own company, despite being the founder. This resulted in a substantial financial and emotional loss.