Which businesses use an accounting equation? The answer is: virtually all of them. From the smallest sole proprietorship tracking its simple finances to massive multinational corporations managing complex global operations, the accounting equation—Assets = Liabilities + Equity—forms the bedrock of financial record-keeping. Understanding this fundamental equation is crucial for making informed business decisions, accurately reflecting financial health, and ensuring long-term success. This exploration delves into the diverse applications of the accounting equation across various business structures and sizes, illuminating its significance in different industries.

The accounting equation provides a snapshot of a business’s financial position at any given time. Assets represent what a company owns (cash, equipment, inventory), liabilities represent what it owes (loans, accounts payable), and equity represents the owners’ stake in the business. The equation’s balance—the fundamental accounting principle—ensures that every transaction is accurately recorded, maintaining a consistent and reliable representation of the business’s financial reality. This foundational understanding is critical for accurate financial reporting, effective financial planning, and attracting investment.

Introduction to the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation is a fundamental concept in accounting, forming the bedrock of the double-entry bookkeeping system. It provides a concise representation of a company’s financial position at any given point in time, illustrating the relationship between its assets, liabilities, and equity. Understanding this equation is crucial for accurate financial reporting, effective decision-making, and overall business success.

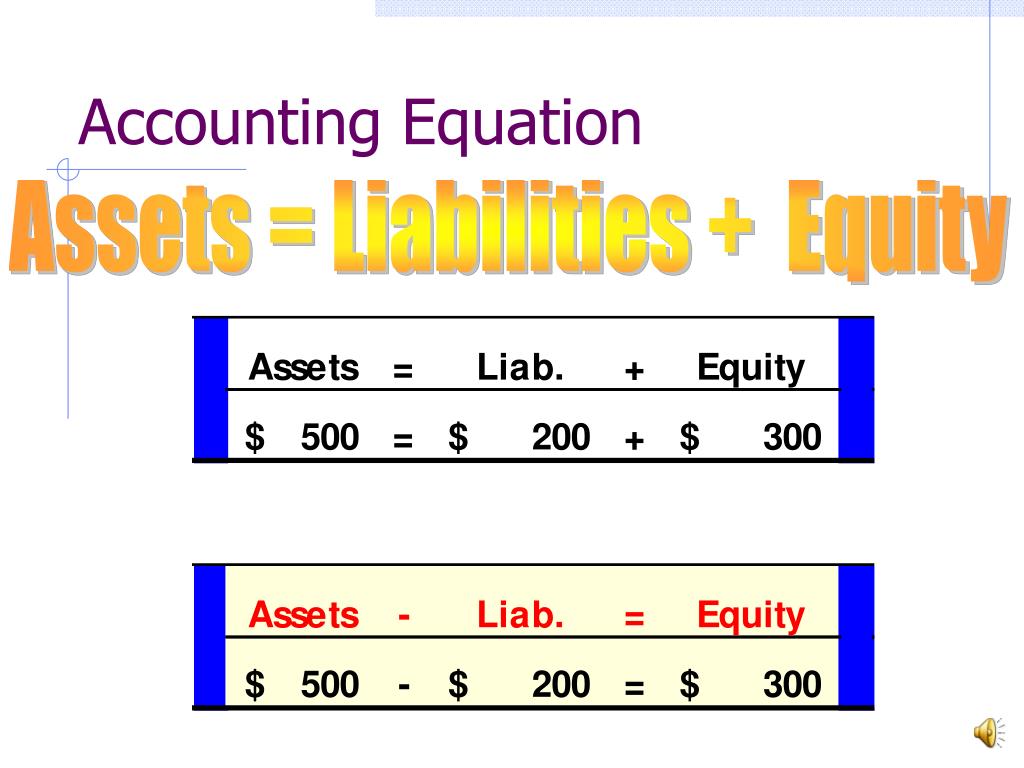

The accounting equation states that a company’s assets are always equal to the sum of its liabilities and equity. This can be expressed mathematically as:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This equation reflects the basic accounting principle that every transaction affects at least two accounts, maintaining the balance.

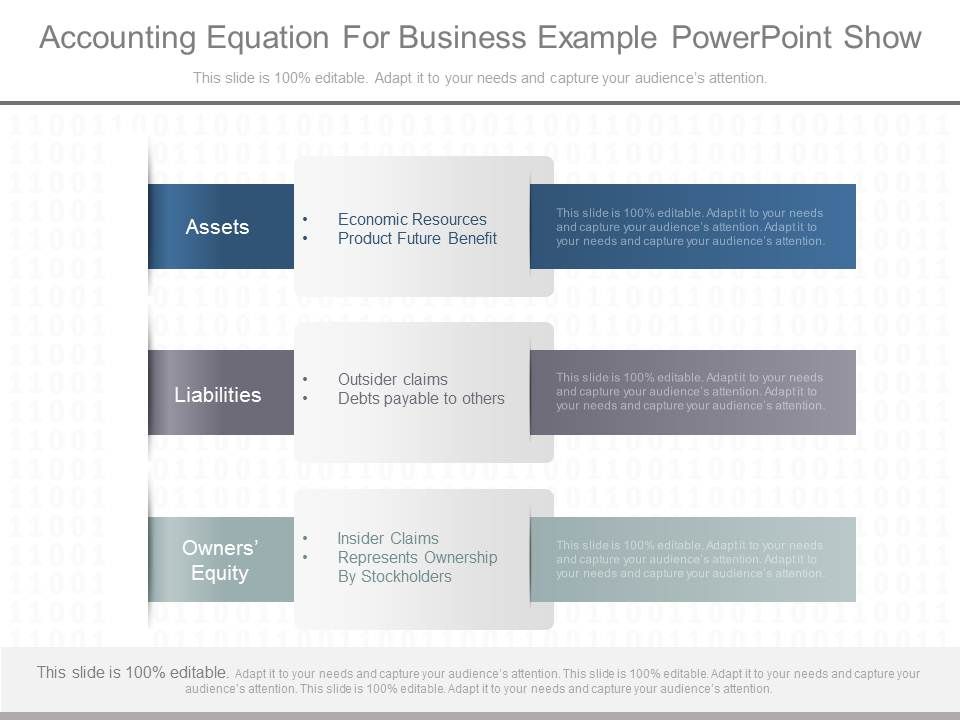

Components of the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation comprises three key components: assets, liabilities, and equity. Assets represent what a company owns, liabilities represent what a company owes, and equity represents the owners’ stake in the company. A clear understanding of each component is essential for interpreting a company’s financial health.

Types of Assets, Which businesses use an accounting equation

Assets are economic resources controlled by a company as a result of past transactions or events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity. Examples include:

- Current Assets: These are assets expected to be converted into cash or used up within one year. Examples include cash, accounts receivable (money owed to the company), inventory (goods available for sale), and prepaid expenses (expenses paid in advance).

- Non-Current Assets: These are assets expected to provide benefits for more than one year. Examples include property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), intangible assets (patents, copyrights), and long-term investments.

Types of Liabilities

Liabilities are obligations of a company arising from past transactions or events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits. Examples include:

- Current Liabilities: These are obligations due within one year. Examples include accounts payable (money owed to suppliers), salaries payable, and short-term loans.

- Non-Current Liabilities: These are obligations due in more than one year. Examples include long-term loans, bonds payable, and deferred tax liabilities.

Types of Equity

Equity represents the residual interest in the assets of an entity after deducting all its liabilities. For a sole proprietorship or partnership, equity is often referred to as owner’s equity. For corporations, it’s referred to as shareholder’s equity. Examples of equity accounts include:

- Common Stock: Represents the investment made by shareholders in the company.

- Retained Earnings: Represents the accumulated profits of the company that have not been distributed as dividends.

Importance of the Accounting Equation for Business Operations

Understanding the accounting equation is crucial for several reasons. It allows businesses to:

- Monitor Financial Health: By tracking changes in assets, liabilities, and equity, businesses can assess their financial health and identify potential problems.

- Make Informed Decisions: The equation provides a clear picture of a company’s financial position, enabling informed decisions regarding investments, financing, and operations.

- Ensure Accurate Financial Reporting: The equation ensures that the balance sheet, a key financial statement, is always balanced, providing a reliable representation of a company’s financial position.

- Improve Financial Management: By understanding the relationships between assets, liabilities, and equity, businesses can improve their financial management practices and optimize their resource allocation.

Types of Businesses Utilizing the Accounting Equation: Which Businesses Use An Accounting Equation

The accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, is a fundamental principle underpinning all business accounting. Its application, however, varies depending on the business structure and size. Understanding these variations is crucial for accurate financial reporting and effective business management. This section explores how different business types and sizes utilize this core equation.

The accounting equation remains constant regardless of the business structure. However, the composition of assets, liabilities, and equity will differ based on the legal and operational characteristics of each business type.

Business Structures and the Accounting Equation

Sole proprietorships, partnerships, corporations, and limited liability companies (LLCs) all employ the accounting equation. The key difference lies in how ownership and liability are structured, impacting the equity component of the equation. In a sole proprietorship, the owner’s personal assets and liabilities are often intertwined with the business. A partnership distributes ownership among partners, affecting equity representation. Corporations and LLCs offer limited liability, separating personal assets from business liabilities, leading to distinct equity structures.

Business Size and the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation’s application remains consistent across small, medium, and large businesses. The difference lies in the scale and complexity of the assets, liabilities, and equity components. Small businesses might have fewer and simpler transactions, resulting in less complex accounting records. Large corporations, conversely, manage significantly more assets, liabilities, and equity, requiring sophisticated accounting systems and potentially specialized accounting personnel. The underlying equation, however, remains the same.

Industries Utilizing the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation is indispensable across various industries. Its application provides a clear picture of a company’s financial health, regardless of its specific operations. Retail, manufacturing, and service businesses all rely heavily on accurate accounting to manage their finances effectively. The following table illustrates examples of assets and liabilities within different industries and business types:

| Industry | Business Type | Example of Asset | Example of Liability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retail | Sole Proprietorship | Inventory (clothing, electronics) | Accounts Payable (to suppliers) |

| Manufacturing | Corporation | Factory Equipment | Bank Loan |

| Services | LLC | Client Receivables | Salaries Payable |

| Technology | Partnership | Intellectual Property (software) | Deferred Revenue |

Practical Applications of the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, is more than just a fundamental accounting principle; it’s a dynamic tool used throughout the life cycle of a business. Its practical applications extend far beyond simply balancing a balance sheet; it underpins financial statement preparation, informs critical financial decisions, and provides a framework for understanding the financial health of any organization.

The accounting equation’s power lies in its ability to illustrate the interconnectedness of a company’s financial resources and claims against those resources. Understanding this relationship allows businesses to make informed decisions, monitor performance, and effectively communicate their financial position to stakeholders.

Financial Statement Preparation

The accounting equation is the bedrock of the balance sheet, one of the three core financial statements. The balance sheet presents a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. The equation ensures that the total assets (what a company owns) always equal the combined value of its liabilities (what it owes) and equity (the owners’ stake). Any transaction impacting the balance sheet must maintain this equality. For instance, if a company purchases equipment with cash, assets (equipment) increase, and assets (cash) decrease by the same amount, maintaining the equation’s balance. The income statement, while not directly derived from the equation, is indirectly linked. Net income from the income statement increases retained earnings, a component of equity on the balance sheet, thereby impacting the accounting equation.

Financial Decision-Making

The accounting equation plays a crucial role in various financial decisions. Investment decisions, such as acquiring new equipment or investing in research and development, require careful consideration of how these actions affect the equation. Financing decisions, including obtaining loans or issuing equity, directly impact both liabilities and equity. Dividend decisions, where a portion of profits is distributed to shareholders, reduce retained earnings and consequently, equity. By analyzing the potential impact of each decision on the equation, businesses can assess its feasibility and overall financial implications. For example, a company considering a significant expansion project might use the equation to model the impact of increased assets (new facilities and equipment) on its financing needs (increased liabilities through loans) and its overall equity position.

Illustrative Scenario: Impact of Changes on the Accounting Equation

Consider a small bakery, “Sweet Success,” that starts with $10,000 in cash (asset) and $5,000 in owner’s equity (equity). Its initial accounting equation is: $10,000 (Assets) = $0 (Liabilities) + $10,000 (Equity). Sweet Success then takes out a $5,000 loan (liability) to purchase an oven ($5,000, asset). The new equation reflects these changes: $15,000 (Assets) = $5,000 (Liabilities) + $10,000 (Equity). The equation remains balanced. If Sweet Success then uses $2,000 of its cash to buy ingredients, its cash decreases to $8,000, but its inventory (another asset) increases by $2,000, again maintaining the balance of the equation. This simple scenario highlights how every transaction, no matter how small, affects the equation, emphasizing its importance in tracking and understanding a company’s financial health.

Limitations and Considerations of the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation, while fundamental to financial reporting, possesses inherent limitations that prevent it from fully capturing the true economic value of a business. Its reliance on historical cost and its inability to incorporate certain crucial aspects of business value mean that the equation provides a snapshot of financial position rather than a complete picture of a company’s worth. Understanding these limitations is crucial for accurate financial analysis and decision-making.

The accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, is based on the principle of double-entry bookkeeping. Every transaction affects at least two accounts, maintaining the balance of the equation. However, this system relies heavily on historical cost accounting, meaning assets are recorded at their original purchase price. This fails to reflect the current market value of assets, which can fluctuate significantly over time. Furthermore, many valuable aspects of a business, such as brand reputation, intellectual property, and employee expertise (intangible assets), are not readily quantifiable and therefore often excluded from the equation. This omission leads to a significant underestimation of the true worth of a business, especially in knowledge-based industries.

Intangible Assets and Market Value Discrepancies

The accounting equation primarily focuses on tangible assets—those with physical substance, like property, plant, and equipment. Intangible assets, such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and goodwill, are often recorded at cost or not at all, despite potentially representing a substantial portion of a company’s overall value. For instance, a tech startup with a revolutionary algorithm might have minimal tangible assets but immense potential value derived from its intellectual property. The accounting equation wouldn’t accurately reflect this potential due to the difficulty in assigning a precise monetary value to the algorithm. This difference between the book value (as reflected in the equation) and the market value can be substantial, making the equation an imperfect measure of a company’s true worth. A company’s market capitalization, often significantly higher than its book value, reflects this discrepancy.

Potential Discrepancies and Their Causes

Discrepancies in the accounting equation can arise from various sources, including errors in recording transactions, misclassifications of accounts, and the use of different accounting methods. For example, a simple error in recording a sale could lead to an imbalance in the equation. Similarly, incorrectly classifying an expense as an asset would also distort the equation’s balance. The adoption of different accounting standards (e.g., IFRS vs. GAAP) can also lead to variations in how assets and liabilities are valued, resulting in differences in the reported figures. Furthermore, the timing of revenue recognition and expense matching can influence the equation’s balance at any given point. For example, delaying the recognition of revenue could artificially inflate equity, while accelerating expense recognition could decrease it.

Factors Influencing the Accuracy of the Accounting Equation

Several factors can impact the accuracy of the accounting equation. The accuracy of the underlying data is paramount. This includes the reliability of source documents, the competence of accounting personnel, and the effectiveness of internal controls designed to prevent and detect errors and fraud. The choice of accounting policies and methods, such as depreciation methods for fixed assets or inventory valuation techniques, can also significantly affect the figures reflected in the equation. External factors, such as changes in market conditions and economic downturns, can influence the value of assets and ultimately impact the equation’s balance. Finally, the timely and accurate recording of transactions is essential. Delays or omissions in recording transactions can lead to inaccuracies and misrepresent the financial position of the business.

Visual Representation of the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, is fundamental to accounting. Visual representations significantly enhance understanding of this core principle and its dynamic nature in reflecting business transactions. These visuals help to clarify the interconnectedness of the three main components and their impact on the overall financial position of an entity.

The accounting equation can be effectively visualized using both a balance sheet-style diagram and a flowchart illustrating transactional impact.

Accounting Equation Diagram

This diagram represents the accounting equation as a balanced scale. The left side represents Assets, while the right side represents the combined weight of Liabilities and Equity. The scale remains balanced because the total value of Assets always equals the total value of Liabilities plus Equity. Imagine a simple scale with a clearly marked fulcrum in the center. On one side, clearly labeled “Assets,” we can depict various asset categories such as cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and equipment, each represented by a weight proportionate to its value. On the other side, we have two distinct sections, one labeled “Liabilities” and the other “Equity.” Similar to the Assets side, each liability (accounts payable, loans, etc.) and equity component (common stock, retained earnings) is represented by weights, ensuring the total weight on the “Liabilities + Equity” side always equals the total weight on the “Assets” side. This visual emphasizes the fundamental balance inherent in the equation and the interconnectedness of its components. Any change on one side necessitates a corresponding change on the other to maintain equilibrium.

Flowchart Depicting Transactional Impact on the Accounting Equation

A flowchart provides a step-by-step illustration of how transactions affect the accounting equation. This dynamic representation demonstrates the constant balancing act maintained throughout business operations.

The flowchart begins with the initial state of the accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Each subsequent step represents a transaction. Arrows indicate the direction of change for each component. For example:

Step 1: Initial State: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. (The equation is balanced.)

Step 2: Transaction: The company receives a loan of $10,000.

* Assets (Cash) increase by $10,000.

* Liabilities (Loans Payable) increase by $10,000.

* Result: Assets ($10,000 increase) = Liabilities ($10,000 increase) + Equity (no change). (The equation remains balanced.)

Step 3: Transaction: The company purchases equipment for $5,000 using cash.

* Assets (Equipment) increase by $5,000.

* Assets (Cash) decrease by $5,000.

* Result: Assets (net change of $5,000 increase in equipment) = Liabilities (no change) + Equity (no change). (The equation remains balanced.)

Step 4: Transaction: The company earns revenue of $2,000.

* Assets (Cash or Accounts Receivable) increase by $2,000.

* Equity (Retained Earnings) increases by $2,000.

* Result: Assets ($2,000 increase) = Liabilities (no change) + Equity ($2,000 increase). (The equation remains balanced.)

Each transaction is represented by a box containing the details of the transaction. Arrows flow from the box to the relevant components of the accounting equation (Assets, Liabilities, and Equity), indicating whether the component increases or decreases. The flowchart concludes with the final state of the accounting equation, which again demonstrates the balance. This visual representation clearly illustrates how every transaction affects at least two elements of the equation, maintaining the fundamental equality throughout. This dynamic representation is crucial for understanding the real-time impact of financial activity on a business’s financial position.

Advanced Applications of the Accounting Equation

The fundamental accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, transcends basic bookkeeping. Its power lies in its ability to provide a robust framework for sophisticated financial analysis, forecasting, and strategic decision-making, particularly in complex business scenarios. Understanding its advanced applications unlocks deeper insights into a company’s financial health and future prospects.

Analyzing Financial Ratios and Performance Indicators

The accounting equation forms the bedrock for numerous crucial financial ratios. For example, the debt-to-equity ratio (Total Liabilities / Total Equity) directly reflects the proportion of a company’s financing derived from debt versus equity, a key indicator of financial risk. Similarly, the current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) assesses a company’s short-term liquidity, indicating its ability to meet its immediate obligations. Analyzing these ratios, derived directly from the equation’s components, allows for a comprehensive assessment of a company’s financial performance and stability. A consistently high debt-to-equity ratio, for instance, might signal excessive reliance on debt financing, increasing the risk of insolvency. Conversely, a consistently low current ratio may indicate potential liquidity problems. These analyses provide valuable insights for investors, creditors, and management alike.

Utilizing the Accounting Equation in Forecasting and Budgeting Processes

The accounting equation is instrumental in the forecasting and budgeting processes. By projecting future asset levels based on anticipated sales growth, investment plans, and debt acquisition, businesses can estimate their future liabilities and equity positions. This allows for proactive financial planning, ensuring sufficient resources are available to meet anticipated obligations and fund future growth initiatives. For example, a company projecting significant sales growth might forecast a corresponding increase in accounts receivable (an asset) and potentially increased inventory (another asset) to meet the anticipated demand. This projection, in turn, informs the budget for working capital requirements. Such forecasting, grounded in the accounting equation, allows for proactive financial management and risk mitigation. A mismatch between projected asset growth and funding sources could be identified early, allowing for adjustments in the business plan.

Applying the Accounting Equation in Mergers and Acquisitions

The accounting equation plays a critical role in evaluating mergers and acquisitions. Analyzing the balance sheets of merging entities allows for a thorough assessment of the combined entity’s financial position. The process involves carefully integrating the assets, liabilities, and equity of both companies to determine the resulting financial structure. For instance, in a merger, the combined assets would represent the sum of the individual companies’ assets, while liabilities and equity would be similarly aggregated. However, potential synergies and asset write-downs need to be considered. Identifying potential redundancies in assets (e.g., overlapping facilities) or intangible assets requiring impairment (e.g., diminished brand value post-merger) requires a detailed analysis based on the accounting equation, ensuring a realistic valuation of the combined entity. Post-merger integration, including adjustments for goodwill and other intangible assets, requires a careful application of the accounting equation to reflect the true financial picture of the combined company.